Among the many types of art affected by COVID-19, theater has taken one of the sharpest blows. One of the beauties of theater is its live aspect — the audience can take in the setting firsthand and return another night for the promise of something new. Although virtual performances have attempted to reignite the flame of theater, they have had difficulties captivating viewers the way an in-person show does. However, this is not the case with Theater Emory’s newest production “The Infernal Machine,” as directors Donald McManus and Mary Lynn Owen have taken control of their virtual landscape to produce a lively and atmospheric show.

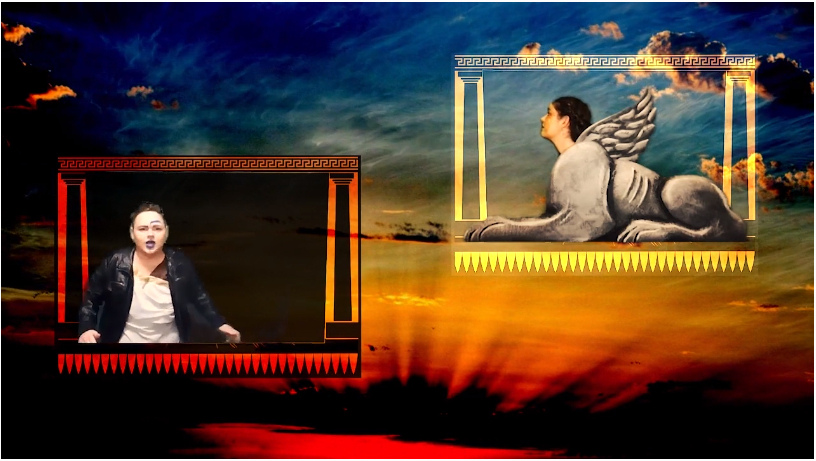

“The Infernal Machine,” written by French playwright Jean Cocteau in 1932, is an adaptation of the Oedipus myth. The play follows Oedipus (Nic Bogan (19Ox, 21C)) and Jocasta (Caitlin Hargraves), the queen of Thebes who is mourning the loss of her husband Laius (Christopher Hampton). After murdering the Sphinx (Sabrina Parra Díaz (22C)), Oedipus develops a relationship with Jocasta and their pasts come to light. Although the play has similarities with the precedent work of Sophocles, it does set itself apart. In addition to including new characters such as Anubis (Johnny Hall (24C)), Cocteau also altered the personalities of characters, such as Oedipus’ narcissism and the Sphinx’s empathy.

One of the many favorable aspects of this production worth noting is its impeccable acting. The cast brings enthusiastic energy to this play, with each member offering captivating performances. Bogan’s performance as the vain Oedipus shone and played a substantial counterpart to the caring rendition of Jocasta by Hargraves. Díaz’s thoughtful performance as the Sphinx, a character who’s grown tired of killing people, is juxtaposed with her associate Anubis. Even the most minor of characters, such as the matron (Colleen Carroll (21C)), whose depressing backstory pushes the Sphinx to despise death, act as substantial additions thanks to the cast’s passion for the script.

Oedipus (Nic Bogan) facing off against the powerful Sphinx (Sabrina Parra Díaz). (Emory Wheel, Eythen Anthony)

Two difficulties that come from producing plays in the confines of Zoom are the lack of movement and the reduced backdrop options. Unless a play is written to be performed virtually, it can be hard for an actor to move in the ways a script requires. However, “The Infernal Machine” cleverly worked around these issues thanks to the use of a green screen. Not only did this allow for the actors to emulate movement, as characters could be positioned walking alongside each other, the green screen also reduced the prominence of Zoom’s rectangular borders. When the borders were seen, their purposes were grounded in the play, such as when the Sphinx’s border was placed high on the screen to symbolize her soaring above Oedipus. Plus, the green screen ultimately increased the number of backdrops available for the play to use, which ranged from the castle wall of Thebes to the bedroom of Queen Jocasta. “The Infernal Machine” was not hindered by its limitations; rather, the play fostered creativity, allowing for an inventive production.

Along with the green screen, another technical choice that fits nicely with the virtual setting is the use of animated openings that precede each act of the play. Every act begins with the haunting singing of Tara Zhang (23C), who explains the events that led up to the scene. Animated scenes that either build upon the backdrop or connect with Zhang’s words accompany this singing. Although these introductions are a small thing, they prove that there are benefits to having a virtual performance over an in-person one. These instances not only visually enhance the production, but they allow the viewer to further insert themselves in the ancient city of Thebes.

Although the technical feats stand out in this performance, they do not overshadow the superb costume, makeup and prop design. The costumes consist mainly of white tunics, but there are a few exceptions such as the royal purple of Jocasta’s dress and the well-crafted mask of Anubis. While there is some repetition with the white tunics, the makeup stands out among the uniformity. Each design is unique to the character (such as Trojan helmets for the soldiers), and the creative decisions fit with the inventive production. The props are another example of the play’s innovation, even though there aren’t many. For instance, one of the best examples is a handheld mirror that has the center cut out, enabling a character to look through it and act as if they’re looking at their reflection. Creative decisions act as a common theme in “The Infernal Machine,” proven by these cases.

With the introduction of the COVID-19 vaccine, it’s safe to say that there will be a return to in-person theater. While this is an exciting thought for most, let us not neglect the online productions that have found ways to carry the energy of live performances. “The Infernal Machine” is a standout show that demonstrates that, no matter the circumstances, theater will continue to persevere.

"machine" - Google News

April 27, 2021 at 06:41AM

https://ift.tt/3gEW1bd

'The Infernal Machine' Provides Hope for Virtual Theater - The Emory Wheel

"machine" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VUJ7uS

https://ift.tt/2SvsFPt

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "'The Infernal Machine' Provides Hope for Virtual Theater - The Emory Wheel"

Post a Comment