Part 1: Seeing the vision of where and how machining and Industry 4.0 meet

Change is hard. Whether it’s learning a new software package or setting up a new model of machine tool, many of us wonder at some point, “Is all this hassle worthwhile?” Change can also be risky, raising the specter of lost time, revenue, and reputation. The consequences become even greater when you’re among the first to dip your toes into the state-of-the-art waters, a pioneer who spends more time figuring out which way to go and how to get there than actually getting something done.

Or so it seems.

This resistance to change might explain why the manufacturing industry lags behind others in terms of technology adoption. One example of this is the wealth of productivity boosters available today—offline tool presetting, quick-change workholding, toolpath simulation software, and automated material handling, to name a few—systems that have been around for decades but are still not widely used. Is it their seemingly high cost that’s holding us back, or fear of change?

Now along comes Industry 4.0 and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). Suddenly, manufacturers are being asked to string Ethernet cable across the shop floor, install servers and routers and hire teams of IT people to manage the flood of Big Data coming their way. The result? Industry 4.0 will only increase the technology gap between manufacturers striving for higher efficiency and visibility and the ones that see nothing wrong with the status quo, provided they can ship products on time and make a reasonable profit.

If you’re among the latter, most industry experts would tell you it’s time to embrace change, and perhaps the best place to start is by using data to drive the decision-making processes in your shop. That’s according to Jeff Rizzie, director of digital machining at Sandvik Coromant, Fair Lawn, N.J., who suggested these efforts have become much easier over the past few years. Where people once collected data manually (if at all) and collated it in Excel spreadsheets or homemade databases, the advent of MTConnect and networked machine tools—together with advanced analytics and remote monitoring platforms—has eliminated this drudgery. Leveraging these tools, though, requires a fundamental change in the way we manage the shop floor.

No Time for Tribal Knowledge

“Think about the causes of manufacturing variation and how we deal with them today,” Rizzie said. “For example, you might have two CNC lathes that are identical except for the fact that tool life on one is always a little worse than the other, or a batch of steel just came in that’s a bit harder to machine than the last time you ran it. In either case, the machinist will usually compensate based on his or her experience—tweaking feed rates or dropping spindle speeds or whatever is needed to get the process stable. And there it stays, possibly dragging down future productivity because we typically solve for the worst case, rather than using data to determine the root cause and then correct it.”

Worse, the lessons learned from these experiences are often kept close to the vest by whoever discovered them, and the person holding this tribal knowledge will eventually retire or find another employer. At that point, those left behind will need to reinvent the wheel. Compound this unfortunate situation with the departmental silos of information that exist in so many companies and the result is inefficiency, inaccuracy, and duplication of efforts. Wouldn’t it be better if we could somehow capture all this tribal knowledge and eliminate its associated waste? This is the heart of Lean Manufacturing, a production method that’s nearing its 100th birthday but has yet to be universally adopted.

“We as an industry don’t have a great handle on what’s happening with our machine tools, our people, our processes,” Rizzie added. “In fact, I’d say the flow of information today is no better than it was back in 1980 when I first walked into a shop. The technology is certainly better, but our data management? Not so much. We have departmental KPIs (key performance indicators) that conflict with one another. We don’t share data between the shop floor and the front office. And where we do share information, many of us are still relying on phone calls, email, texts, and even fax machines to do so. All of that must change if we’re to see significant improvement in our manufacturing operations.”

Connecting Production Machines

Bijal Patel agreed. A senior digital machining specialist at Sandvik Coromant, he points to the need for increased connectivity throughout the industry, even among those manufacturers ranked as world class. “It’s ironic that a company might spend a million dollars on a CNC multitasking lathe or horizontal machining center, put it on the shop floor and ensure that lines for electric and compressed air are installed, but the Ethernet cable is an afterthought,” Patel said. “And yet, a much lower cost item like a laptop or tablet PC needs a Wi-Fi password to do anything useful.” The message is clear: the Internet is increasingly vital to our daily lives, and we will soon reach a point where it will be vital to our manufacturing equipment as well.

Hold on, though—practically any machine shop or production facility will remain operational if its Internet line gets cut. The machine tools will keep cranking out parts, and the UPS truck will arrive each afternoon to carry them away. Is connectivity to the outside world so vital after all?

Perhaps not, unless that same factory is highly automated and its management team would like to receive notifications when something has gone awry during the night. And what about the factories that want to capture the tribal knowledge just discussed, or eliminate the departmental silos of information? Can any meaningful Industry 4.0, IIoT, or even Lean initiative take place without Internet-dependent services, such as cloud-based computing and data storage, remote monitoring and machine diagnostics, intelligent analytical software, and access to digital tooling information?

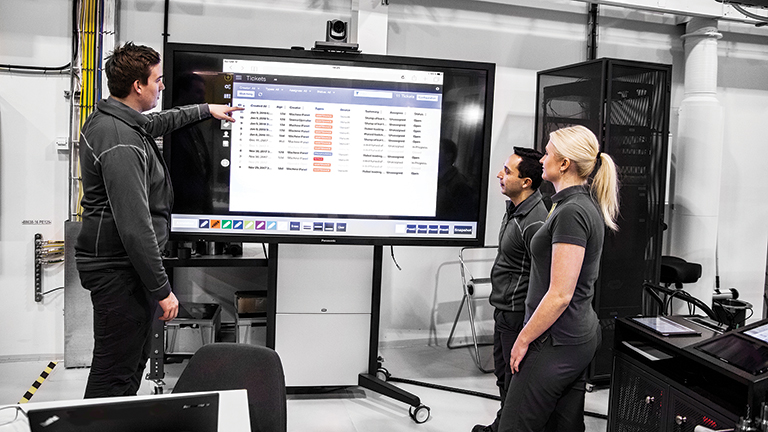

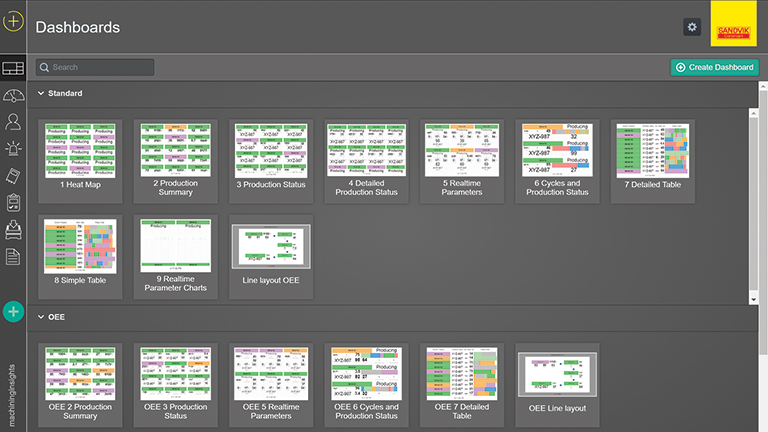

“Without access to real-time machine and process-related data, Lean and other continuous improvement efforts will yield only incremental improvements; the best way to maximize these initiatives is to collect and then analyze this data using an automated, cloud-based software tool,” Patel said. “From Sandvik Coromant’s perspective, that tool is CoroPlus MachiningInsights.”

Assembling the Industry 4.0 Pieces

“Oh, great,” you’re thinking. Another software package, another implementation, more money spent on consultants, more monthly expense. Maybe so, but before diving into the dollars and cents of any analytics tool, consider the justification. “I know a lot of manufacturing engineers and programmers who walk in each morning, sit down at their desk, and think, ‘Okay, what’s today’s fire?’” Patel said. “Or maybe they come back from lunch and there’s a broken end mill or tagged part waiting for them, along with a note that says, ‘Come out and see me when you get in.’ So they walk out and talk to the operator, only to find that no one’s quite sure why the machine made that awful noise, but everything seems to be working now.”

Random events like this seldom happen in a data-driven manufacturing company, and when they do, there are digital breadcrumbs leading to the problem’s source. Data is key to any kind of process improvement. Without it, there are no root cause analyses, no fishbone diagrams—only the often inconclusive tedium of talking to people and trying to figure out what went wrong.

This is why any Kaizen event starts with people collecting data about their processes, then brainstorming how to make them better. The downside to this approach, however, is obvious: manual data collection takes time. When Lean first started becoming popular, people had no choice but to write things down. Computers and Excel spreadsheets accelerated these efforts, although it was still a manual undertaking that detracted from the business of making parts. Industry 4.0 and the IIoT has changed all that, or will when large numbers of shops begin embracing it. That’s because once CNC machine tools have been connected to the corporate network and coupled with solutions like MachiningInsights, data collection is entirely automatic.

Sounds great, but what does that actually mean to my shop? What data is available from the typical lathe or machining center? And what if my newest CNC is 10 years old—will it still offer usable information?

These are all excellent questions, ones that Patel answers regularly. “Even a 10- or 12-year-old machine provides a wealth of relevant data,” he said. “Axis and spindle loads, feed rate override status, part count, machine alarms—these are just a few examples of valuable information that’s easy to obtain from practically any machine tool. And for shops with older machines, these can be equipped with aftermarket electronics to make them network capable. Simply put, there’s no longer a reason to collect this data manually.”

Setting the Bar

Machine tool data is just part of the equation, however. Shops must also capture operator input, job information, tool performance, and more. Knowing that the load on the Z axis of Machine #5 spiked at 3:02 PM might be a great clue in a machine shop detective story, but you won’t need to be Sherlock Holmes if the operator was able to document that he got busy helping Bob and forgot to change the insert at the prescribed time, or that they were testing a new modular drill and the performance was less than advertised. This is the power of an Industry 4.0-capable analytics and machine monitoring solution.

Such solutions give shops a far greater grasp of what’s going on. Most will soon discover that the 73 percent OEE (overall equipment effectiveness) figure they’ve been touting at the weekly production meetings is more like 41 percent or even less, especially when you take into account scrapped parts. They’ll have actual numbers on how much time is spent making chips, how long parts are sitting in inspection, the current rejection rate, the average changeover time, where are the shop’s biggest bottlenecks, what lot number of material was being run last week when tool life went in the tank…the list goes on. Big data helps you see the big picture.

Let’s say you have that big picture—what then? Rizzie has a few suggestions, starting with the OEE calculations just mentioned. “I’ve worked with a number of shop people who, once you start walking them through the true numbers, are shocked at how little their machines cut metal each day,” he said. “The machines are powered up, they’re consuming air and electricity, there are people or robots available to operate them and they may even be executing a program, but they’re not actually producing good parts. And once you realize that, you can use the same data to understand why. That’s just one of the many areas you can start to address when you have a digital strategy in place.”

Picking the Low-Hanging Fruit

Julio Vasconcelos, engineering manager for Sandvik Coromant’s production facility in Mebane, N.C., has such a strategy, and said that it’s a game-changer. He and his team started their digital journey about two years ago. They began by evaluating the different software options and where in their 50-person shop they should apply them, ultimately deciding to start with some low-hanging fruit: cycle time.

“Soon after installing MachiningInsights, we noticed that many of our run times were longer than what the CAM system said they should be,” he said. “We started digging and found that when an operator ran into trouble—maybe there was some chatter, maybe tool life wasn’t all that great—their solution was to adjust the overrides until the problem went away, and then leave them there for the entire job. Do the math and you’ll quickly realize that a feed rate reduction of 20 percent means 20 percent fewer parts at the end of the day.”

Vasconcelos explained that they set the system to send an alert to the engineering department anytime it detected a feed rate or spindle override was not at 100 percent for more than 10 minutes. The engineers would then call the operator or walk down to the production floor and find out why, thus giving them a chance to correct the problem instead of hiding it with a temporary fix. In several instances, this gave them an extra day per week of machining time.

Similarly, the team began using the software to document the causes of machine downtime. “We’d tried previously with Excel, with paper, with homegrown systems—nothing was effective until we installed iPads at each machine and encouraged the operators to provide reason codes anytime the machine wasn’t running,” he said. “Within a few months, we went from 45 percent downtime to less than 20 percent, with better tool life and cycle times to boot. That, and the operators were happy because there were fewer surprises—they began to feel like they’re part of the solution, rather than someone who applies Band-Aids all day.”

In Part 2 of “The Connected Shop”—Where Machining and Industry 4.0 Meet, we’ll explore how to build a business case for a digital transformation, organize resources, and suggest where to get started.

"machine" - Google News

June 22, 2020 at 07:03PM

https://ift.tt/3hS4RQU

The Connected Machine Shop - Advanced Manufacturing

"machine" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VUJ7uS

https://ift.tt/2SvsFPt

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Connected Machine Shop - Advanced Manufacturing"

Post a Comment