The stocky speaker in the blue suit spat venom across the aisle, wagged his finger at the opposition, and took full command of the podium. Cheering erupted from behind him. Booing thundered from the opposing side. His usual slick smile missing in action, he stared down the raucous, angry crowd that was Australia’s Parliament.

This story originally appeared in the September/October issue of Road & Track.

The current raging debate was whether to continue assisting the country’s flailing auto industry. The government was tired of subsidizing Australian carmaking, which employed thousands but had always kept one foot out the door. Ford and Mitsubishi had already left; Nissan had been gone for decades. Imports comprised more and more of the market. Suppliers struggled even as the rest of the economy seemed to be humming along. Much of the debate centered around Holden, the GM subsidiary headquartered in Port Melbourne. The company maintained several local factories but received billions in Australian taxpayer aid to do so, while sending meager profits back to Detroit.

And now Treasurer Joe Hockey was done playing nice. Nostrils flared, finger jabbing the lectern, he leaned into the microphone and made the government’s case. If Holden wanted another dime, Australia needed to know whether the company was in it for the long haul.

“Either you’re here,” he said, “or you’re not.”

The next day, he had his answer. On December 11, 2013, GM announced that Holden would cease production in Australia by the end of 2017. Two months later, Toyota, which had a plant in suburban Melbourne, confirmed it was leaving, too.

And so the winding down began. Factories closed. Employees were laid off. Suppliers pivoted, looking for customers in a manufacturing sector that now barely existed. In early 2020, GM announced it was axing the Holden brand altogether. The news came more as a mercy than a surprise. Australia’s oldest carmaker was dead, as was the country’s auto industry.

The fortunes of factory towns and thousands of jobs went with it. Sixty-nine years of continuous mass production, boarded up. The country was told to move on, forget the automotive sector. But Australia left its indelible mark on the automotive landscape as the birthplace of Mount Panorama Circuit and Mad Max’s Pursuit Special. Oz was hot-rod utes and factory super-sedans on Mustang platforms, the land where the V-8 dream never died. Until it did.

Perhaps the end was unavoidable, a consequence of factors far beyond the control of any automaker or transportation minister. Much of it was structural. The Aussie auto industry looked healthy from the outside, but doing business domestically had always depended on investment from foreign automakers and subsidies from the Australian government.

“Australia, like the U.S., came together as a federation,” says Dr. Russell Lansbury, an emeritus professor at the University of Sydney and an industrial relations scholar. “And one of the big issues was free trade versus protectionism.”

There were two main political parties, one advocating for free trade, one for protectionism. Protectionism won out, with the government that came into power in 1901 choosing to defend its manufacturing sector. Agriculture and mining, Lansbury says, were the country’s natural industries. Manufacturing would need artificial support to survive.

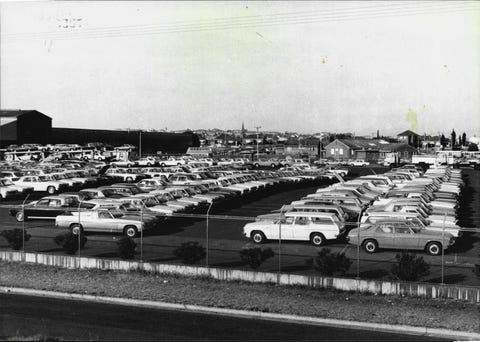

When postwar industrial players like GM, Ford, Renault, Toyota, and Chrysler sought access to Australia’s growing market, they hit a steep tariff wall. With import duties as high as 57.5 percent, the automotive market essentially required local assembly. Carmakers bought in. Nearly a dozen manufacturers built vehicles in Australia at the industry’s peak. Before long, entire supply chains were centered in Australia, with second- and third-tier suppliers manufacturing fasteners, electronics, and miscellaneous components. Inside this self-contained ecosystem, the industry could turn out dozens of models with major components sourced directly from Australian firms.

Car culture and motorsport flourished. The local tribalism of Holden and Ford families gave rise to one of the all-time great automotive rivalries. Simple, reliable workhorses like the Toyota Land Cruiser roamed through the Australian Outback. V-8 family sedans revved at stoplights next to truck-like, quintessentially Australian utes. An honest-to-God, home-grown racing series sprouted; V-8 Supercars thundered over and around Mount Panorama, promoting the culture and producing dozens of top-tier drivers. “The Americans have a gun culture. We have a car culture,” Mad Max director George Miller famously said.

The boom lasted for decades. Holden, a coachbuilder that became GM’s Australian arm in 1931 and the company that gave Australia its first mass-produced car, grew to support seven operational factories and 24,000 workers. Holden would eventually become Australia’s flagship brand, but it was far from its only large-scale manufacturer. By the time the industry peaked in the Seventies, Ford, Nissan, and Toyota all had plants in the country.

The industry was vibrant, but by most objective measures, it was never very big. Annual automotive production in Australia topped out at around 500,000 cars per year. That’s about the annual production of BMW’s Spartanburg, South Carolina, plant. Hyundai’s largest complex, in Ulsan, South Korea, can make 1.5 million cars annually. Even at their apex, Australia’s plants never got close to today’s megafactories.

How could they? With the rise of the modern globalized economy, Australia’s manufacturers had to confront certain economic realities, chiefly national buying power. Australia has a smaller GDP than New York state. Without large-scale vehicle exports, only the most successful cars were produced at a large enough scale to justify a localized supply chain. This left domestic automakers in a fierce continuous fight for every bit of market share during the Seventies and Eighties.

Renault bowed out in 1981. Chrysler sold its Australian business to Mitsubishi. Volkswagen and British Leyland ceased local operations. Meanwhile, the same protectionist policies buoying the auto industry were drawing retaliatory tariffs, impacting far more profitable sectors of the Australian economy. Eventually, the government decided it was time to open the gates.

Enter Senator John Button, federal Minister for Industry and Commerce. Depending on who you ask, his plan to overhaul the Australian auto industry was either a cursed moment or a necessary evil. Either way, it’s considered the point of no return.

Beginning in 1985, the government encouraged auto manufacturers to gradually consolidate and attempt to become more competitive with the outside world. Import tariffs would taper with the goal of leaving three robust manufacturers locally producing about six models between them. Button’s scheme to cull the herd worked: By the early 2000s only Mitsubishi, Toyota, Ford, and Holden were left standing. And then Mitsubishi closed its last plant in 2008.

Still, it remained tremendously difficult for automakers to turn a profit in Australia. The biggest enemy of localized production, experts say, was the emergence of the Toyota Production System. Also known as “lean” or “just-in-time” manufacturing, the method relies on close coordination with suppliers to eliminate shipping and storage waste. Ideally, a gigantic factory acts as a nexus, fed by a network of suppliers working in unison. Automakers across the globe quickly adopted and standardized lean methods. But with aging facilities scattered across a sprawling continent—and insufficient sales to justify four factories, let alone four manufacturers—implementation in Australia wasn’t possible.

Neither was Button’s vision of propping up a trio of globally competitive carmakers. But the Australian auto industry wasn’t brought down by a lack of investment, the rise of just-in-time manufacturing, or the challenges of a unique local market. It was a mining boom, and the foreign money that followed.

“At the same time the car industry was announcing its closure… iron ore and coal were being sold to China and people were making pots of cash,” says Royce Kurmelovs, journalist and author of The Death of Holden. “All of these smaller companies were making heaps of money. And that changed the currency rate to the point where you basically had manufacturers losing money every time they exported cars.”

As foreign money enters an economy, the value of that country’s currency balloons, increasing the relative price of the nation’s exports. That impacts automakers worldwide, but Australian industry is particularly susceptible due to the volatility of its national dollar. As billions poured in from resource extraction between 2001 and 2011, Australian currency doubled in value. Suddenly, the shift towards a profitable, large-scale vehicle exporting scheme was out of the question.

This partially explains why fantastic V-8 muscle cars from Down Under rarely came stateside. Only tastes of what we were missing—a GTO-badged Monaro, a Commodore dressed as a Pontiac G8—slipped through.

“I think that it was the perfect storm for the car industry, the fact that the [Australian] dollar went sky-high and made manufacturing uncompetitive across a range of things, not just the car industry,” says Dr. Lansbury. That currency boom, he argues, played a much larger part in the demise of Australian automaking than the role of organized labor.

Though many have scapegoated unionized workforces, Dr. Lansbury ranks it low on the list of reasons that the industry floundered. Kurmelovs agrees. So does Dr. Harry C. Katz, a professor of collective bargaining at Cornell University’s School of Industrial & Labor Relations.

“Australian wage rates in the auto sector were not unusually high,” says Dr. Katz. “The unions as well were not particularly militantly adversarial. They were tough… but you didn’t hear, ‘we have about a zillion disciplines going on’ or ‘we have walkout strikes’ or ‘we have union leaders we can’t even talk to.’ That’s just not what I experienced when I talked to the managers of the various plants in the Nineties.”

Blaming labor is too easy. So is laying the corpse at the door of faceless bean counters or stuffy executives in Detroit boardrooms callously dispatching people’s livelihoods. It’s more comfortable to see it as a failure of people, of greed, than it is to confront what it says about the core struggle of automotive enthusiasm.

Because Australia had the enthusiasm. Try as they might, automakers can’t always blame the buyers. Australia-only sedans moved in massive numbers. Even as sales fell with the decline of the industry as a whole, Holden was still selling almost 25,000 Commodores a year when the factory packed up. In a nation with stratospheric gas prices and a world dominated by bland crossovers, you have to admire the dedication.

Australia tried to avoid reality for as long as it could. The government spent like hell to balance automaker books: Holden received 1.8 billion Australian dollars in subsidies and grants between 2001 and 2012; Ford and Toyota each reportedly took over a billion. It wasn’t enough. Profits were tiny and rare, losses massive and routine. Ford succumbed in 2013, which made it even harder for Holden and Toyota to survive; with so few manufacturers, equipment and supplier costs went up. Hat in hand, they asked the government for more.

But the economic reality was unavoidable. Australia, once a thriving automotive fiefdom, was ultimately a country too small for domestic production and too expensive for export manufacturing. Fed up with subsidizing companies that could never grow to succeed, the Australian government called their bluff. They didn’t want to hand out more money without a commitment, without a plan. Cards on the table time.

Hockey demanded to know if the automakers were there for good. They weren’t.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

"auto" - Google News

September 18, 2020 at 09:47PM

https://ift.tt/3mvMROB

Land Gone Under: How Australia's Auto Industry Fell Apart - RoadandTrack.com

"auto" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Xb9Q5a

https://ift.tt/2SvsFPt

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Land Gone Under: How Australia's Auto Industry Fell Apart - RoadandTrack.com"

Post a Comment