Welcome to Thomas Insights — every day, we publish the latest news and analysis to keep our readers up to date on what’s happening in industry. Sign up here to get the day’s top stories delivered straight to your inbox.

The trend is clear: manufacturing is becoming increasingly automated and less reliant on human labor. But there’s an important caveat: machines can’t repair themselves. This means that in the critical area of maintenance and repair, human-machine contact will never disappear. Additionally, poorly functioning equipment requires more operator interaction as well.

As we focus on keeping employees safe in the midst of this pandemic, let’s not forget the inherent dangers that accompany working on equipment that is not performing its intended function optimally.

There’s Risk Even Before the First Signs of Equipment Failure

If you were to chronicle the lifecycle of a piece of equipment, you would find that the risk to people that engage with the equipment starts to increase even before the first physical signs of failure manifest themselves. As equipment nears the end of its functional life, it starts to show signs of instability.

At first, the equipment may require more frequent adjustments to keep its output consistent and within specifications. As wear advances, those adjustments become more frequent, increasing the risk of an injury. Small variations in raw materials or the operating environment, which were tolerated by the machinery when new, now create outages or off-spec products.

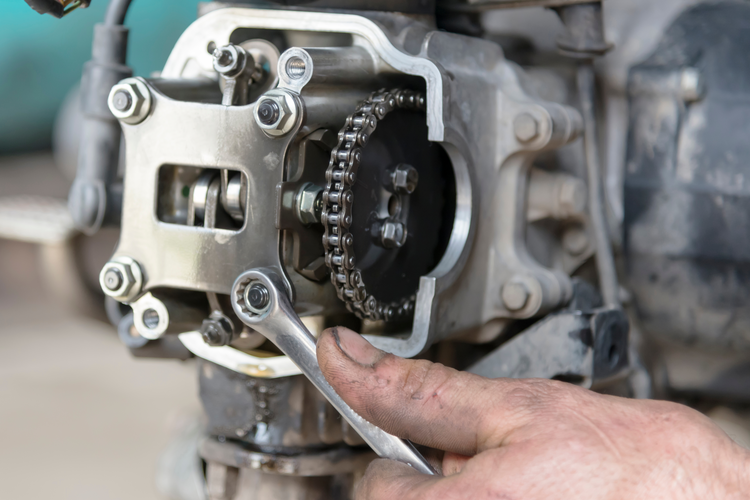

Take, for instance, the infeed of a packer. As the conveyor that feeds bottles of product wears, it may no longer feed those bottles consistently into the packer. Jams start to occur that shut the equipment down. An operator may have to start physically unjamming the bottles and restart the equipment. Perhaps a mechanic gets called to the line to tighten chains or otherwise attempt to alleviate the problem. All of these actions expose individuals to sharp edges, potentially energized equipment, and pinch points. Left uncorrected, the conveyor continues to degrade until it catastrophically fails. These failures can result in flying debris, hot metal parts, sharp edges, and more.

The takeaway is that even in the early stages of malfunctions and equipment wear, serious injuries and even fatalities are possible, especially if the asset catastrophically fails. These human-machine interfaces where an operator or maintenance technician is working to correct a malfunction may be referred to as the “last yard.” This is where the rubber meets the road.

How to Reduce Risks to Workers

Perhaps the most important evolution in automated manufacturing is that the nature of the maintenance and repair function is evolving. From making immediate fixes and repairs to machinery that has failed, front-line maintenance jobs are now part of the process of predicting and preventing breakdowns in the first place.

Fortunately, the advances that result in automated manufacturing processes also have led to high-tech tools that can detect when machinery is in trouble and likely to fail. Augury, for example, manufactures detection devices that monitor machinery and report likely problems before apparent signs of stress. So reliable is the technology that the Hartford Steam Boiler and Inspection Company insures users against repair costs if a machine fails while monitored by Augury’s technology.

But even when problem-detection comes early and averts costly breakdowns, repairs have to be made. In order to realize the benefits that come from automated manufacturing technology — more efficient equipment usage, increased output, and greater productivity — those increasingly important front-line maintenance workers must be able to get those repairs done quickly and safely. Technology is great but even the best machine health intelligence is ineffective until a person closes the “last yard” and implements the fix.

Speed can be accomplished through the technology itself. Systems can order replacement parts, for instance, as soon as a problem is detected so that repairs can be made quickly. Even as industrial and manufacturing equipment becomes more automated, the inherent physics of manufacturing does not change. Making physical objects involves transforming materials, and that usually generates friction and heat, which make for dangerous conditions. Sharp, flaming objects and flying metal shards are all-too-frequent risks when manufacturing equipment fails or requires adjustment.

Continuous machine health monitoring itself is a great boon for safety in that overall man-machine interfaces are greatly reduced, removing considerable danger. But for those maintenance and repair workers remaining on the front lines, danger is still present. Continuously monitoring equipment through automated tools helps reduce those dangers by eliminating small and large failures that can lead to accidents. These tools also permit regular maintenance to be conducted in a non-rushed, safe manner.

Reducing worker risk pays off not only financially in the form of less lost production and lower insurance costs, but also in the form of improved worker health and well-being. What’s more, improving safety is simply the right thing to do.

With fewer people employed in manufacturing and doing ever more important tasks, making the “last yard” safer should be everyone’s priority. To borrow a slogan from my early career days, “Nothing we do is worth getting hurt.”

Image Credit: osobystist / Shutterstock

More from Technology

"machine" - Google News

December 03, 2020 at 12:19PM

https://ift.tt/3qn9Ltx

How to Make the “Last Yard” Safer for Machine Operators, Technicians - ThomasNet News

"machine" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VUJ7uS

https://ift.tt/2SvsFPt

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "How to Make the “Last Yard” Safer for Machine Operators, Technicians - ThomasNet News"

Post a Comment