The prototyping area within KVI’s shop floor. The company is now part of the KMM Group, which formed in 2020 as a joint venture with M&S Centerless Grinding and Meron Medical. Photo Credit: KMM Group

For most of the KMM Group’s employees, the first detailed explanation behind the new, joint-venture company — which until last year existed as three separate manufacturing businesses — came in the form of a blog post written by the company’s co-founder John Shegda. The blog post appeared on the KMM website on June 16, titled simply, “Why the Heck Did We Merge?”

It was a question that some of KMM’s 90-plus combined employees might have been asking. At first glance the merger might not have made sense. Each of the three companies that now composed the KMM Group were second-generation, family-owned manufacturing and machining businesses that were financially sound. The companies’ two leaders were in their early 50s and presumably in the primes of their careers. John Shegda led two of the companies, M&S Centerless Grinding and Meron Medical, while Eric Wilhelm headed up a precision machining company called the KVI Group.

The blog post attempted to answer the questions, Why merge, and why now?

You can read Shegda’s article for yourself, but at a time when machine shop mergers and acquisitions appear to be on the rise, we wanted to ask a few questions of our own. So we sat down with Shegda and Wilhelm and talked through the motivations behind the merger, how the two leaders navigated the process, and the expectations they have for their new joint venture. The conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Modern Machine Shop (MMS): Let's start with a quick background description for each of the three companies that now compose the KMM Group. Briefly describe each of the three companies that merged last year.

John Shegda (JS), co-owner: The K of KMM stands for KVI, or KV Incorporated. That is the company that Eric Wilhelm, my partner, brought into the mix. KVI focuses on all things machining and high-end advanced manufacturing. So, Swiss screw machining, five-axis milling, EDM and toolmaking.

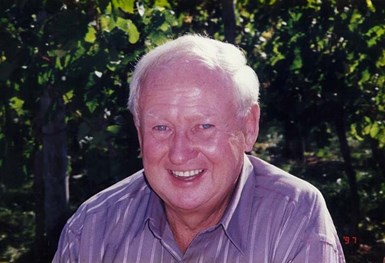

Eric Wilhelm (EW), co-owner: KVI was founded in January of 1977 by my father, Karl Wilhelm, who was a European immigrant tool and die maker. When he first started out, he had a strong technical background in designing and building tools and dies for very thin gummy type materials like band aids, papers, plastics and laminates.

Karl Wilhelm was a European immigrant tool and die maker who founded KVI in Huntington Valley, Pennsylvania in January of 1977. Photo Credit: KMM Group

These required an extremely close tolerance at sometimes less than one ten-thousandth of an inch, and he was able to establish a name for quality in high-precision manufacturing in the area. Early in 1979, he got into wire EDM (electrical discharge machining) and really cultivated an area of expertise in that area over the next few years.

The company continued to grow, servicing the tool and die arena for medical devices, aerospace and automotive, but also EDM for production components in those industries. When I took over in 2000, we started to expand. We still performed the design and engineering required for all the high-precision tooling that we would be challenged to build by our customers, but then expanded into CNC machining. Today we're a full-service design and engineering firm providing DFMA (design for manufacturing and assembly) analysis and focusing on long-term methods of production depending on volumes. We take things from the prototype stage up through production.

JS: From our side, we call my two companies that I brought into the mix, “the grinding group.” It’s just easier to say that rather than Meron Medical and M&S Centerless Grinding.

Meron Shegda was the founder and namesake for Meron Medical and for M&S Centerless Grinding. Meron’s son John now operates the companies, which recently merged with KVI to form the KMM Group. Photo Credit: KMM Group

The ‘M’ and ‘S’ in M&S Grinding are both my dad's initials — the ampersand is a marketing ploy to make it sound like there was more than just one person there. We started in 1957 as the prototypical mom and pop, shall we say, grinding dungeon, from the late ‘50s until really the late ‘80s. And I say that partially tongue-in-cheek but also affectionately. My dad always was a perfectionist. He was an uncompromising man. A brilliant man. In the Philadelphia area, if you needed something done right, you went to M&S.

I joined the company in 1987 after I graduated college with no intention of staying. But he put me through school, and I said that I would give it a year. Of course, I got bitten by the manufacturing bug and I elected to stay. I was employee number three in 1987 — 30 years after the company was founded.

From there we grew pretty substantially. I talked my older brother into coming into the business with me in the late 80s, early 90s. And he and I ran the business and grew it similarly to my dad until the mid 2000s, when I understood that I needed to run it significantly differently than what I was doing because I was going to burn out. We heavily invested in equipment and started to systemize our operations. I bought my brother out in 2008 — right ahead of when everything came crashing down. You know, timing is everything.

In 2013 I spun off Meron Medical. Meron was my father's name, so both companies are named after dad, basically. We started Meron Medical because we were finding ourselves doing more and more medical device work for large medical OEMs. We operate in a very specialized area of medical device grinding, including guidewire grinding or core-wire grinding for catheters. Basically, we're grinding wires that get inserted into your brain or your heart.

MMS: How did you two meet each other, and who first brought up the idea of a merger? How did that conversation evolve?

JS: Funny enough, the idea of a merger was brought up as we were closing down a bar about five years ago over gin and tonics. It was actually a part-time business development guy who said, “You guys ought to just merge your companies.” And Eric and I kind of looked at each other like, “Huh. You know that's not a bad idea!” But the real inception of that idea was that our fathers were colleagues in their businesses. M&S Grinding was a vendor for KVI. So Karl knew my dad, Meron, and Eric and I knew each other from just doing business together. You know, we always had a healthy respect for the others’ companies. And so that was the initial point at which we met.

The shop floor of Meron Medical, now part of the KMM Group. Photo Credit: KMM Group

EW: I can't tell you how many times John and I would run into each other. Either we were a customer to M&S or Meron or we were a vendor, and we'd always just kind of chat about little things. There always seemed to be an alignment in so many different ways and with the things we believed in. It was almost a little scary how similar our lives were as we were growing up, just sharing the same beliefs and wanting to make a similar impact. And that alignment has made for a great merger.

JS: In fact, one of our colleagues who we saw at an event early last year before COVID said to us, “You guys are like cousins.” And now we occasionally call each other ‘Cuz’. We're not blood relatives but it just kind of fits.

About 10 years ago we both joined a group called Vistage, which is a worldwide business development group for owners of small and mid-sized companies. Basically, we act as each other's board of directors. And through that we got to know each other's businesses better and started thinking about things bit differently.

MMS: What were your succession strategies before the merger, or before you had the idea to join forces? Had each of you decided whether you wanted to keep your companies going beyond your retirement?

EW: Before the KMM merger, my exit strategy was to seek an equity group that had parallel business interests. The goal would have been to try to find a company that shared our culture but had a much larger presence in the manufacturing community. The culture aspect is an incredibly important part to me. The plan was to develop a solid management team and always be transparent with them about what the long-term goals were. I was going to be in this at least until my mid 60s. That was the original plan.

JS: When I spun Meron Medical off of M&S, the intention was to grow Meron Medical and then sell it. That would have provided me what I needed to retire. For M&S, I was kind of hoping to be able to ease off and put in into the hands of the employees. When it became apparent that I wasn't going to pass it down to my family, I wanted to pass it to the employees through an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP).

MMS: Let's talk about how you strategized to make the merger happen. What were those early conversations like?

JS: We’re both active in Vistage and we both serve on boards of local trade associations. We read about the industry and see a lot of progressive things happening in manufacturing. You start seeing industry 4.0 and the things that are coming down the pike at you, and what was going through my mind was, Man, this is not going to be easy to navigate as a mid-sized business. I kept getting feedback from people indicating that you might have to be a pretty sizable company in order to be a standalone 10 years from now.

At the same time, we get solicited on a regular basis. We attend the medical device trade shows and get listed all the time by equity groups. We’ve had some of our customers try to buy us. That's kind of the way of the world, and you walk down the path a little bit and see what it means. So when things started to gel, Eric had been talking with an equity group and said to me, “You know, these guys are kind of interesting, you might want to talk to them, too.” And so we started talking to them together, very loosely at first. How long did that go on, Eric? Like a year and a half?

EW: Yeah, I would say about 18 to 24 months. These people were just an avenue to take some risk off the table and also get that larger company vision and foresight into where industry was heading. That was a driver for me.

JS: Like Eric said, we started thinking about the equity group as a matter of taking a little bit of risk off the table now, so we can grow the hell out of the businesses with some money backing for a period of years. But what kind of made it turn, though, happened spring of 2019. We took a trip out to where the equity group is located and they showed us a presentation. It was a good presentation and a good trip, but we started realizing that this was a risk — and not just for us. The equity group was intrigued by our two companies, but this was a risk for them too. So they were taking some valuation off the table in light of that.

When we got back to our Vistage group, a few of our members basically said, “Why are you not doing this yourself? They're discounting you. Why don't you at least get it running and prove that you can do it. And then if you want to take on equity after a couple of years, then at least you're not going to get discounted because you'll have proven its success.” We thought that was a good idea. It made us both stop and think about the direction we were heading. And then we really started going full on and writing up plans for doing this ourselves.

John Shegda and Eric Wilhelm, co-founders of the KMM Group. The two men have known each other for most of their adult lives and decided to merge their companies in 2020. Photo Credit: KMM Group

MMS: Talk about any logistical challenges during the merger process itself. What were the sticking points that had to be worked through?

JS: Honestly, I can't believe how smooth it has been. It's a little freaky. We were pouring over legal documents from about October through the end of December (of 2019), going through iterations of shareholders agreements and doing due diligence. And I mean, we spent hours and hours and hours together and we didn't have one argument. Not one. Not even a disagreement, really, on anything through that whole process. I found that quite amazing.

There really was almost no overlap in capability. It was almost like two jigsaw puzzle pieces coming together. You start going down the line and there was no duplication of efforts.

EW: I will say one thing that has really helped the merger of these organizations is the amount of communication that John and I provide to our people. As an example, in most cases that I've heard of when a company is sold, everything is on the quiet. Nobody knows anything until suddenly, one day, there is an article in the paper, or the owner is introducing a new owner. We took a much different approach. In early November of 2019 we actually talked to our companies, together, and explained what we were doing and why we were doing it. That it was a benefit for the organizations for the long term to remain competitive.

JS: There was also a lot of alignment on multiple levels. You have KVI that takes the material and does the machining. And then you have M&S and Meron, which does the high precision grinding at the end. So there really was almost no overlap in capability. It was almost like two jigsaw puzzle pieces coming together. KVI had a general manager. We didn't have a general manager. M&S grinding has a controller. KVI didn't have a controller. You start going down the line and there was no duplication of efforts. There weren't a lot of hard decisions, like, “We're gonna have to let this person go,” or, “I have to fight to keep this person.” That made things easier as well.

MMS: A lot of independently owned shops are not going to be so lucky to be in a situation like yours, where you know your prospective partner and you partner’s family as well as you two have. What advice do you have for any machine shop owners who might be searching for an exit strategy down the road?

JS: I think the biggest step and the first piece of advice is to simply start thinking about it. This is not something that you can do in a year. Not even merging, but just putting a succession plan together. We had a Vistage speaker that talked about different ways in which you can exit your business. You can be a passer, you can be a squeezer, or you can sell. You can pass it on to another generation; you can squeeze the hell out of it and have an auction at the end; or you can sell it as a going concern. It just depends on what you want. Do you want to leave a legacy? Do you want it to go on to another generation, whether that generation is related or extended family in the form of your employees? Or do you just want to take as much money out of it as you can? Once you decide what direction you want to go, there are resources out there including big accounting firms that really do well with these transitions, as well as business development groups like Vistage. There are also folks who specialize in this area that can help coach you through the process and do it the right way.

EW: One of the greatest things I've learned personally, being in Vistage for years, is that there are a ton of people out there with the same problems, but there is always an answer. There's always a way to make progress. Sometimes you gain that progress through a trusted advisor or a peer group, or sometimes it’s through reading. There's a great book called “Dance in the End Zone” by Patrick Ungashick that could be a platform for people to begin with. Go out there and find a trusted advisor in this arena and see what you can learn. Ask questions, or let them ask questions of you, and figure out what you have to do.

I think if you start with the end in mind, and lay out the different steps and create a timeline for yourself, you can get there.

RELATED CONTENT

-

How To Machine Aircraft Titanium: The 8-To-1 Rule For Finishing Walls And Ribs

Part of a series of articles on more efficient machining of pockets in titanium parts, this article makes the case for a tool with many cutting edges, and describes how best to apply it.

-

When Spindle Speed is a Constraint

Though it won’t replace high speed machining, Boeing sees “low speed machining” as a viable supplement to higher-rpm machines. Using new tools and techniques, a shop’s lower-rpm machining centers can realize much more of their potential productivity in milling aluminum aircraft parts.

-

Composites Machining for the F-35

Lockheed Martin’s precision machining of composite skin sections for the F-35 provides part of the reason why this plane saves money for U.S. taxpayers. That machining makes the plane compelling in ways that have led other countries to take up some of the cost. Here is a look at a high-value, highly engineered machining process for the Joint Strike Fighter aircraft.

"machine" - Google News

February 26, 2021 at 02:05PM

https://ift.tt/3svHdOQ

Starting with the End in Mind: An Exit Strategy for Machine Shops - Modern Machine Shop

"machine" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2VUJ7uS

https://ift.tt/2SvsFPt

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Starting with the End in Mind: An Exit Strategy for Machine Shops - Modern Machine Shop"

Post a Comment