-

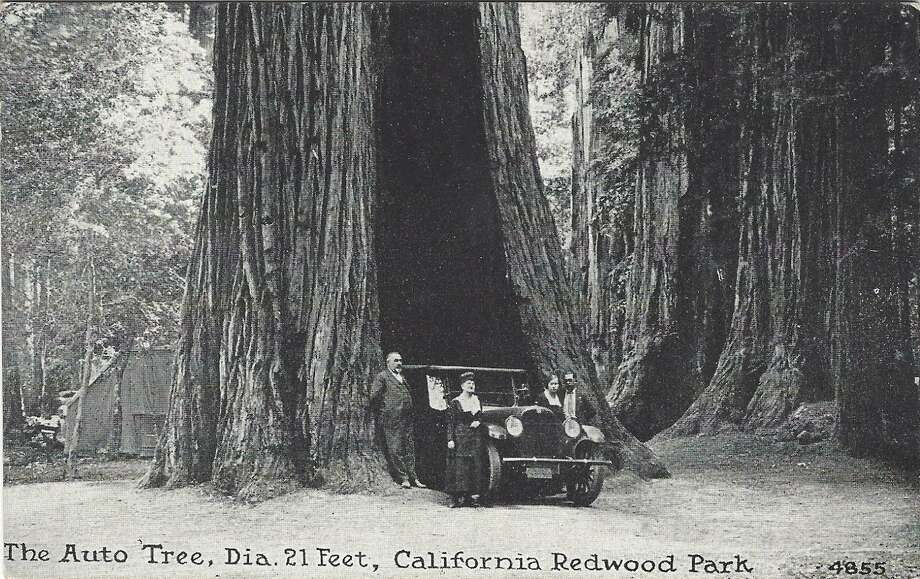

The Auto Tree at California Redwood Park, c. 1920.

Photo: Santa Cruz Public LibrariesThe Auto Tree at California Redwood Park, c. 1920.

The Auto Tree at California Redwood Park, c. 1920.

The Auto Tree at California Redwood Park, c. 1920.

Elise Scripps is worried about a tree.

Eight years ago — before anyone imagined that California’s wildfires could get so bad — the San Jose naturalist volunteered as a docent at Big Basin Redwoods State Park, leading hikes around the Redwood Loop. The short trail near the visitor center was the park’s most popular attraction, and there Scripps introduced visitors to some of the region’s tallest and widest old-growth coast redwoods: the Mother of the Forest tree, a towering 293-footer, and the Father of the Forest tree, 251 feet tall and 18.47 feet across.

It was Big Basin’s magnificent trees — the longest contiguous stand of old growth redwoods south of San Francisco — that in 1902 led to the formation of the state park, California’s first. Scripps loved every tree in the park, but one of her favorites wasn’t on the loop: the Auto Tree. When the tours were over, she would visit on her own sometimes.

Estimated to be more than 1,500 years old, the Auto tree was one of the oldest trees in the park and it stretched 282 feet in the air from not just one but two trunks. Over time the tree had endured so many fires that its heartwood had burned out, leaving its interior hollow and distinguished by a large scar. It seemed miraculous to Scripps, but somehow the tree was still alive, and continued to grow. Even more amazing, the gap seemed to be shrinking over time, a tree healing its own wound.

“It really embodied a redwood and its ability to triumph,” she says. “I loved walking into that tree and looking up.”

An old-growth redwood tree named "Mother of the Forest" is still standing in Big Basin Redwoods State Park, Calif., Monday, Aug. 24, 2020. The CZU Lightning Complex wildfire tore through the park but most of the redwoods, some as old as 2,000 years, were still standing.

Two weeks ago, lightning set off the largest conflagration in the region’s recorded history — the CZU Lightning August Complex fire. It tore across more than 83,000 acres in the Santa Cruz Mountains, leveling Big Basin’s historic headquarters, main lodge, ranger station and many other structures, and extending over all 18,000 acres of the park.

Scripps knew that visitors’ recollections of Big Basin would live on, as would the majority of the robust redwoods. Its structures would be reimagined and rebuilt. Sometime in the future even this massive fire will be only a memory.

Still, Scripps wondered: Did the Auto tree survive?

Fire burns in the hollow of an old-growth redwood tree in Big Basin Redwoods State Park, Calif., Monday, Aug. 24, 2020. The CZU Lightning Complex wildfire tore through the park but most of the redwoods, some as old as 2,000 years, were still standing.

If Elizabeth Hammack was a gambling woman, she would bet it’s still standing, she said last week. Hammack is Big Basin’s manager of interpretation and education, and she’s worked for California State Parks for the last 35 years.

“Here’s what I can tell you,” she said. “The redwoods’ middle name is resilience.”

In Latin, the second part of their scientific name — “sequoia sempervirens” —means “ever living,” and the trees can live for more than 2,000 years. Coast redwoods have few natural enemies and thick, flame-resistant bark. Even when their heartwood catches fire they often persist, with an inner layer of bark preserved and continuing to nourish the tree. The coast redwoods have survived countless natural wildfires as well as burns intentionally set by the native Ohlone people, who used controlled fire to effectively manage the land.

In the 1800s, when early white settlers encountered redwoods hollowed out by fire, they would fence their geese or small domestic animals inside, and the trees became known as “goose-pens.” Later in the century, entrepreneurs began cutting through some of the larger trees, converting them into drive-thru tourist attractions. Although people loved cruising through the magnificent giants in their wagons, stagecoaches and eventually automobiles, the unnatural tunneling sapped the trees' strength and even caused some to topple.

Although there were plans to tunnel the Auto tree, they were never carried out, and instead it became a more eco-friendly “garage tree.” Visitors backed their vehicles into the Auto tree’s goose-pen and posed for photographs.

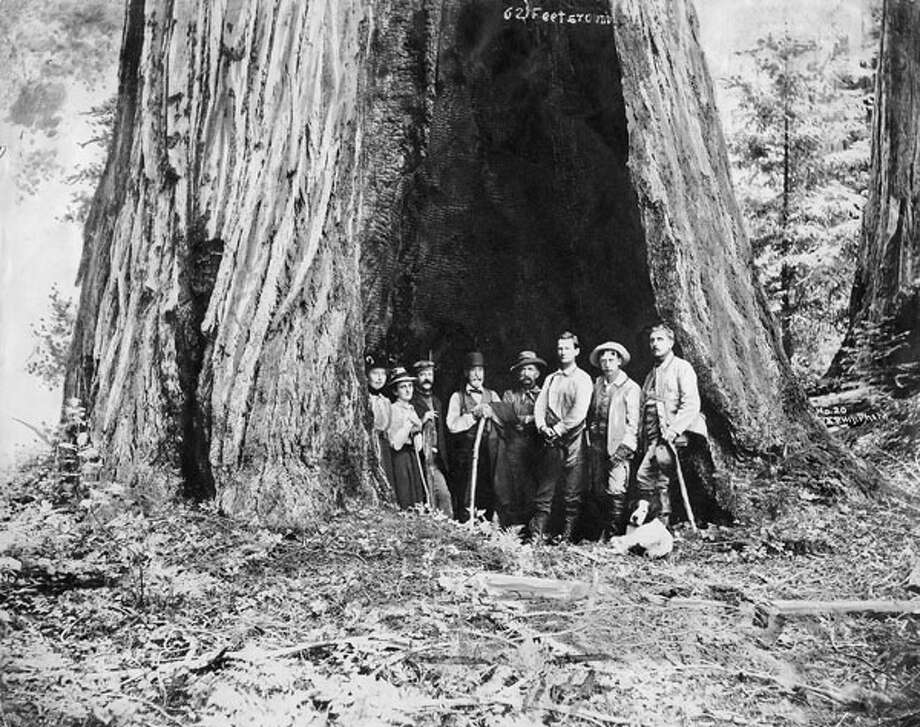

Some members of the Sempervirens Club standing in the Auto tree, including, from left, Louise C. Jones, Carrie Stevens Walter, J. F. Coope, J. Q. Packard, Andy Baldwin, Charles W. Reed, W. W. Richards, and Roley, c. 1890s.

In 1900 the Sempervirens Club, an organization that formed to save coast redwoods from being logged out of existence, famously photographed the tree. The image helped persuade California’s legislature to purchase 3,800 acres of mostly old-growth redwoods and in 1902 created the state’s first park, initially dubbed California Redwood Park. The acquisition helped birth California’s conservation movement, paving the way for the creation of many more state parks within the Santa Cruz Mountains and far beyond.

In the decades that followed, the park boundaries expanded and a lodge, the Redwood Inn, opened in 1920, though some families preferred camping outside for 50 cents a night, often staying all summer. In 1927 the park was renamed Big Basin Redwoods State Park, and in the 1930s the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps built the park’s headquarters out of redwood logs and stone. They also erected bridges and cabins, cut trails, created a wildly popular swimming pool, and built an amphitheater and a nature center. In the 1940s Leonard Penhale, the park’s first naturalist, filled the center with shells, insect specimens and taxidermy.

Over time, as more and more people came to the park to behold the majesty of the trees, the park grew to include a restaurant, a general store, a barber shop, a gas station, a post office, tennis courts and a dance floor.

Sometime during the 40s, taking photos beside cars within the Auto tree fell out of favor, and the park placed stanchions in front of its hollowed out trunk. These days, the practice is not noted in the park’s literature and the Auto tree does not appear on maps. But Scripps knows its location well, just north of the headquarters, or rather, what used to be the headquarters.

After the CZU Complex fire had done its worst, an outpouring of memories were shared by park visitors on social media: People who had fallen in love in Big Basin and posted engagement photos taken among its redwoods, or told stories of wedding ceremonies cradled within their awe-inspiring beauty. Children who first learned to build fires and camp told of teaching their own children the same lessons amid the trees. A man who had run ten miles through the pouring rain to photograph Big Basin’s waterfall at its most torrential. A woman who had hiked Big Basin and been inspired to make a candle with its scent, which has now sold out.

Sarah Moody, owner of Gypsy Vine, was inspired to make a Big Basin-scented candle after an epic trip to the state park in 2016. The candle is currently sold out.

The memories are endless, and like many of the coast redwoods, they survive.

Hammack, the manager of interpretation, is one person who would be more than justified in grieving the loss of Big Basin as we know it. She created every one of the park’s interpretive panels, all of which burned. On the day the fire took the park, she had just signed off on the design for a facelift of the nature center, a $1.3 million project that included interactive exhibits that would allow visitors to explore the redwoods from the point of view of local wildlife.

Now, that is all gone. The historic headquarters, the celebrated lodge, the nature center, the ranger station, the store, the maintenance shop, the cabins and campground bathrooms, along with innumerable irreplaceable specimens and artifacts all burned to ash.

Instead of dwelling on the loss of the park’s structures, Hammack has decided to focus on cleaning up and rebuilding, looking toward a future when the smoke clears. While nobody is sure yet what that looks like, rebuilding the park’s infrastructure will likely require a multi-year, multi-million-dollar effort. But Hammack still has the text for the panels, and the design plans for the new nature museum. And the fundraising has already begun.

“We’ll follow in the footsteps of the redwoods and be resilient,” Hammack says.

The fireplace of the Nature Lodge Museum and Store at Big Basin Redwoods State Park stands among the devastation Friday, Aug. 28, 2020, in Boulder Creek, Calif., wrought by the CZU August Lightning Complex, which destroyed nearly all buildings and burned thousands of trees at the park.

On Friday afternoon, California State Parks still hadn’t completed its survey of the damage, as the fire was still burning and many areas remained inaccessible. But information officer Jorge Moreno did send an update on the status of the coast redwoods.

The Mother and Father of the Forest were both affected by the fire but remain generally healthy, according to the report. The old-growth stand near the entrance to the park experienced a range of fire intensities. The upper crowns of some trees burned while other trees survived unscathed. The condition of the redwoods deeper within the park is not yet known.

“Although fire is an integral part of creating old-growth forests and maintaining healthy forests, it is unknown how intensely this fire burned throughout the park,” the report stated.

It mentioned only one other redwood by name. Perhaps it was because someone knew its history, or perhaps it was because — like Scripps — somebody had a soft spot for the ancient giant that continued to thrive despite a hole in its’ center.

“The Auto Tree sustained moderate to extensive fire damage, but remains standing,” the report stated.

An old-growth redwood tree named "Father of the Forest" is still standing Monday, Aug. 24, 2020, in Big Basin Redwoods State Park, Calif. The CZU Lightning Complex wildfire tore through the park but most of the redwoods, some as old as 2,000 years, were still standing.

Scripps was delighted by the news. But then again, if the Auto Tree had fallen, she would have been okay with that, too.

She understands that, in theory, a redwood never really dies. Instead, its burls — those gnarled lumps near the bottom — shoot out buds that sprout identical new redwoods. They grow in a circle around the fallen one, nourished by its root system.

It just keeps right on living, reaching for the sky.

Ashley Harrell is an Associate Editor with SFGATE who covers California's parks. Email her at ashley.harrell@sfgate.com.

"auto" - Google News

August 30, 2020 at 06:06PM

https://ift.tt/3gHciZx

Triumph of the Auto tree - SF Gate

"auto" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Xb9Q5a

https://ift.tt/2SvsFPt

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Triumph of the Auto tree - SF Gate"

Post a Comment